The Dunbar Number as a Limit to Group Sizes

byLately I've been noticing the spread of a meme regarding "Dunbar's Number" of 150 that I believe is misunderstanding of his ideas.

The Science of Dunbar's Number

Dunbar is an anthropologist at the University College of London, who wrote a paper on Co-Evolution Of Neocortex Size, Group Size And Language In Humans where he hypothesizes:

... there is a cognitive limit to the number of individuals with whom any one person can maintain stable relationships, that this limit is a direct function of relative neocortex size, and that this in turn limits group size ... the limit imposed by neocortical processing capacity is simply on the number of individuals with whom a stable inter-personal relationship can be maintained.

Dunbar supports this hypothesis through studies by a number of field anthropologists. These studies measure the group size of a variety of different primates; Dunbar then correlate those group sizes to the brain sizes of the primates to produce a mathematical formula for how the two correspond. Using his formula, which is based on 36 primates, he predicts that 147.8 is the "mean group size" for humans, which matches census data on various village and tribe sizes in many cultures. The following chart shows the distribution produced by Dunbar's analysis:

Source: Boston Consulting Group

This number of 150 has become "Dunbar's Number" and has been popularized by various very popular business books such as Malcolm Gladwell's The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference (summary), Duncan J. Watts' Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age (review) and Small Worlds: The Dynamics of Networks between Order and Randomness (review), and Mark Buchanan's Nexus: Small Worlds and the Groundbreaking Science of Networks (review), the ideas from which are the foundation of the various Social Network Services that I've discussed elsewhere in this blog.

Revisiting Dunbar's Number

Lately, Dunbar's number has been taken as a mean size for online networks and groups, as shown in Ross Mayfield's Weblog, where he states:

Network Size Description Distribution Political Network ~1000s Blogs as mass media Power-law (scale-free) Social Network ~150 Blogging Classic Bell-curve (random) Creative Network ~12 Blogs as dinner conversation Dense (equal)

However, Dunbar's work itself suggests that a community size of 150 will not be a mean for a community unless it is highly incentivized to remain together. We can see hints of this in Dunbar's description of the number and what it means:

The group size predicted for modern humans by equation (1) would require as much as 42% of the total time budget to be devoted to social grooming.

...

My suggestion, then, is that language evolved as a "cheap" form of social grooming, so enabling the ancestral humans to maintain the cohesion of the unusually large groups demanded by the particular conditions they faced at the time.

Dunbar's theory is that this 42% number would be true for humans if humans had not invented language, a "cheap" form of social grooming. However, it does show that for a group to sustain itself at the size of 150, significantly more effort must be spent on the core socialization which is necessary to keep the group functioning. Some organizations will have sufficient incentive to maintain this high level of required socialization. In fact the traditional villages and historical military troop sizes that Dunbar analyzed are probably the best examples of such an incentive, since they were built upon the raw need for survival. However, this is a tremendous amount of effort for a group if it's trying not just to maintain cohesion, but also to get something done.

Furthermore, Dunbar specifically restricts himself to physically close groups:

... we might expect the upper limit on group size to depend on the degree of social dispersal. In dispersed societies, individuals will meet less often and will thus be less familiar with each, so group sizes should be smaller in consequence.

My anecdotal evidence generally seems to support the idea that group sizes will usually plateau at a number lower than 150 participants. This comes from 20 years of doing facilitation both on and offline, running several software companies, and running various forums at America Online. In particular, many online communities provide good evidence for Dunbar's Number actually being an upper limit (either due to reduced efficiency or due to increased dispersion).

Dunbar & Online Communities

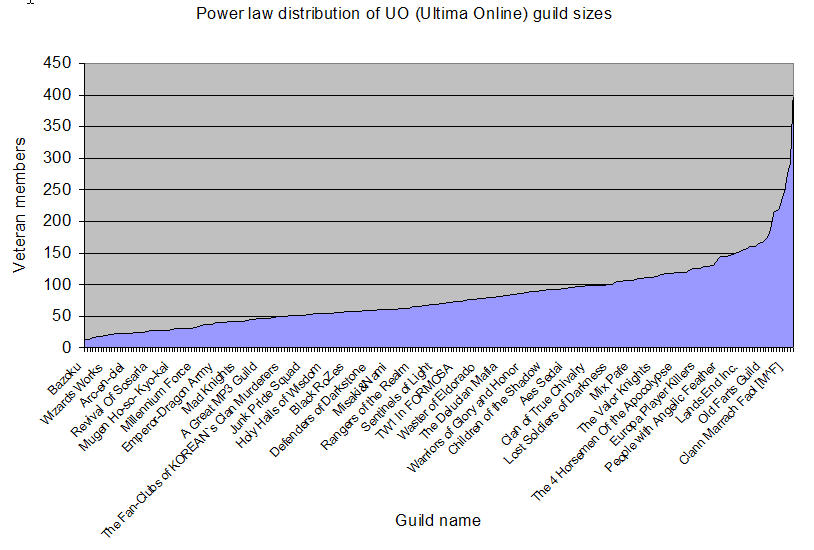

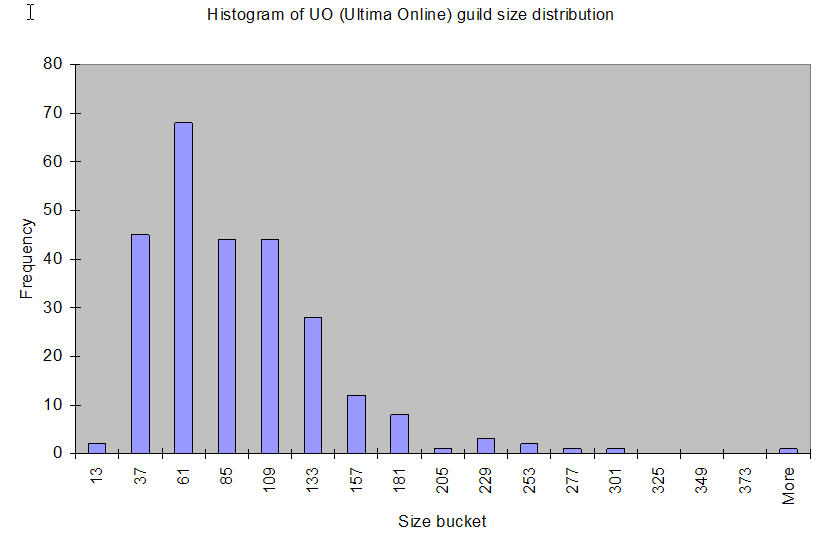

Ultima Online provides one of the best examples of what sizes an online community will support because it's well documented and the overall game size is large enough to generate many smaller communities. If you look at Raph Koster's statistics for the size of groups in Ultima Online, you will see a definite point of diminishing returns at around 150; however, you will also see that most groups are around 60 large.

Jessica Mulligan, executive producer at Turbine Games, confirmed these numbers to me:

The numbers match up with my (currently) mostly anecdotal evidence for Asheron's Call. We have allegiances in the hundreds and even thousands of members, but most of those members are inactive, non-participatory in the group on a regular basis or are mule accounts for farming XP. It is rare to have more than 40 or so active participants in an Allegiance.

I've seen similar limits myself in some of the small online games that Skotos produces. For instance, in Castle Marrach, which is a social-dominant game (i.e. like a MUSH), the game grew quickly until we reached approximately 150-200 active users. However, whenever it grew beyond that number, it always seemed that politics and dissatisfaction would bubble up such that people would drop out, leaving us back close to 150 or 160. (That we would ever exceed 150 is a bit of a surprise, but I think it's due to any number of factors, including a variable 24-hour user base, wherein on a given day we might only see a little more then half of our community members, below Dunbar's Number, and only get up to close to 200 or so over a full week.)

We have had some games at Skotos that do manage to overcome Dunbarrian social limits, prime among them The Eternal City which regularly exceeds the Marrach community by more then double. However, TEC is a much more achievement-oriented game, meaning that people spend much of their time interacting with the environment -- fighting monsters and training skills as it happens -- rather than directly interacting with other players all the time. Thus social limits become less important.

Other online communities that I've had experience with have been more traditional, and thus more closely met my expectations for Dunbar's Number acting as a limit rather than a mean. When I managed the Mac Developer's Forum community on AOL, a forum would start to break down when it reached about 80 active contributors, requiring a forum split before continued growth could occur. Wikis provide another good example; the WikiPedia, one of the largest active Wikis online, appears to have hovered at approximately 150-175 active administrators for over a year, in spite of a huge growth in usage during the same period.

These numbers just keep coming up.

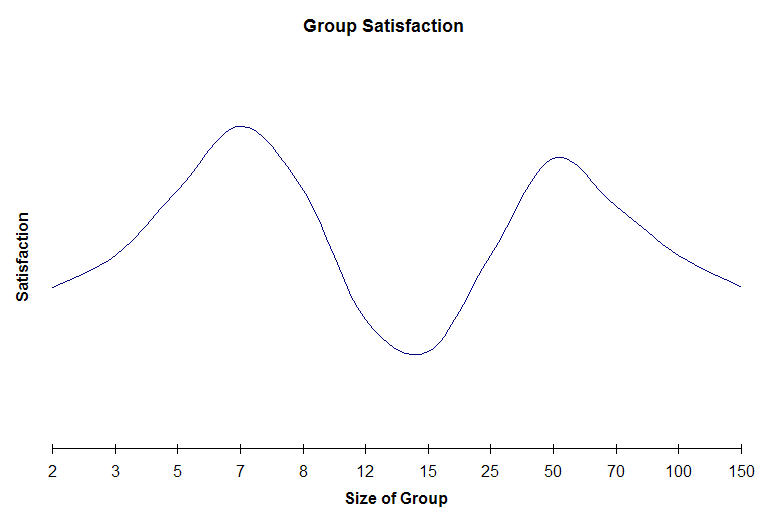

This all leads me to hypothesize that the optimal size for active group members for creative and technical groups -- as opposed to exclusively survival-oriented groups, such as villages -- hovers somewhere between 25-80, but is best around 45-50. Anything more than this and the group has to spend too much time "grooming" to keep group cohesion, rather then focusing on why the people want to spend the effort on that group in the first place -- say to deliver a software product, learn a technology, promote a meme, or have fun playing a game. Anything less than this and you risk losing critical mass because you don't have requisite variety.

Thus Dana Boyd gets it right when she uses the word MAXIMUM in her eTech Talk, not average or mean:

[Dunbar] found that the MAXIMUM number of people that a person could keep up with socially at any given time, gossip maintenance, was 150. This doesn't mean that people don't have 150 people in their social network, but that they only keep tabs on 150 people max at any given point.

Expanding Dunbar's Numbers

To open up the discussion a bit, I'd also hypothesize that Dunbar's Number is just one datapoint in an overall equation describing what group sizes work and what don't. Working our way up from the smallest group sizes, I think we can find many break points, both above and below Dunbar's Number of 150.

In my experience the smallest viable group size seems to be somewhere in the range of 5 to 9.

Looking smaller, we see that a group of 2 can be tremendously creative (ask any parent), but often has insufficient resources and thus requires deep commitment by both parties. Notably, often the difficulty of a 2-person business partnership is compared to that of a marriage. A group of 3 is often unstable, with one person feeling left out, or else one person controlling the others by being the "split" vote. A group of 4 often devolves into two pairs.

In my opinion it is at 5 that the feeling of "team" really starts. At 5 to 8 people, you can have a meeting where everyone can speak out about what the entire group is doing, and everyone feels highly empowered. However, at 9 to 12 people this begins to break down -- not enough "attention" is given to everyone and meetings risk becoming either too noisy, too boring, too long, or some combination thereof. Although I've been unable to find the source, I've heard of some references to a study from the 1950s that says that the optimum size for a committee is 7. Likewise, it's fairly easy for us to see and agree that a dinner party starts to break down somewhere above 7 or 8 people, as do also tabletop games of both the strategic (I prefer 5) and role-playing varieties (I prefer 7). These size limits can be overcome, but require increased amounts of "grooming".

The chasm that starts somewhere between 9 to 12 people can be especially daunting for a small business. As you grow past 12 or so employees, you must start specializing and having departments and direct reports; however, you are not quite large enough for this to be efficient, and thus much employee time that you put toward management tasks is wasted. Only as you approach and pass 25 people does having simple departments and managers begin to work again, as it starts to really make sense for department heads to spend significant time just communicating and coordinating (and as individual departments become large enough to once again allow for the dynamic exchange of ideas that had previously occurred in the original 5-9 member seed group).

I've already noted the next chasm when you go beyond 80 people, which I think is the point that Dunbar's Number actually marks for a non-survival oriented group. Even at this lower point, the noise level created by required socialization becomes an issue, and filtering becomes essential. As you approach 150 this begins to be unmanageable. Once a company grows past 200 you are really starting to need middle-management, but often you can't afford it yet. Only when you get up past that, maybe at 350-500 people, does middle-management start really working, primarily because you've once again segmented your original departments, possibly again reducing them to Dunbar-sized groups.

The following chart shows anecdotal satisfaction ratings for these lower group sizes:

Much of this is probably predicted by Dunbar's model, if you add in the non-survival and dispursed community modifiers that I discuss here. Essentially, as we increase group sizes beyond 80, to 150, 200, or even 350-500, we typically do so by breaking larger groups down into smaller ones, and continually reducing community sizes down to the point where they can be understood and managed by people -- and so efficiency reasserts itself.

Since this post was originally posted, I have added a number of other posts about the Dunbar Number and group size issues: